In the forgotten jungles of Assam, where the monsoon weeps over ancient hills and silence holds dominion over blood, a regiment was born—not of comfort or command, but of conflict. The 8th Gurkha Rifles were not merely soldiers; they were an existential answer to chaos. Armed with the mythic kukri knife, forged in fire and tradition, they carved a century-long legacy in silence.

Their battles did not always win them fame. Their victories were not always paraded. But if truth lives anywhere in the annals of war, it is in the silent, precise cut of a kukri sword wielded by a Gurkha at dawn.

This is the story of a regiment that served from 1824 to 1949, from Burma to Italy, from the jungles of the North-East Frontier to the trenches of France. It is also the story of a blade, the kukri khukuri, inseparable from the identity of the Gurkha, and now, through Himalayan Imports and bladesmiths like Himalayan Blades, offered to a world that barely understands its origin.

The Sylhet Seed: 1824 and the Raising of the 1st Battalion

The genesis of the 8th Gurkhas began in Sylhet, a region then embroiled in the politics of tribal revolt and imperial anxiety. The British East India Company needed local troops who could navigate the terrain—both geographical and cultural—of Assam, Nagaland, and the bordering states. Thus, in 1824, the 16th Sylhet Local Battalion was raised under Captain Patrick Dudgeon.

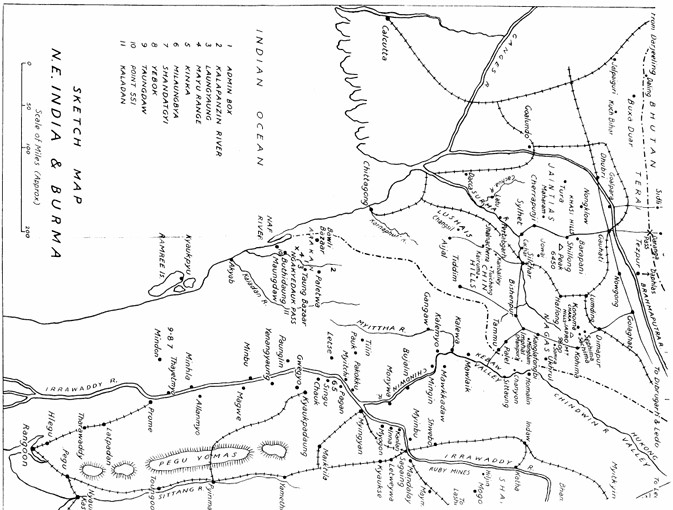

Initially composed of men from the Sylhet region, the Battalion adopted a red coat uniform, soon replaced with rifle green and black facings, reflective of their transformation from militia to precision light infantry. They served in the First Anglo-Burmese War, covering pioneers, road builders, and manning frontier posts against an unforgiving terrain—and equally unforgiving foes.

Enter the Blade: Gurkhas and the Rise of the Kukri

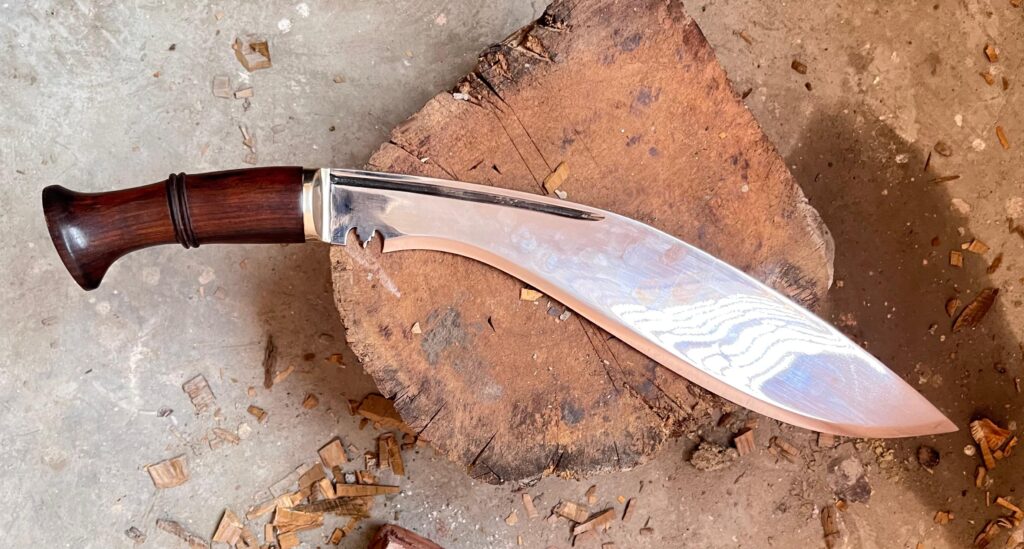

By 1828, recruitment shifted toward Nepali Gurkhas, including men from the legendary Sirmoor and Nusseree Battalions. These weren’t just soldiers—they were mythologies in motion. Along with them came a blade that would become legend: the kukri knife.

This wasn’t a decorative piece or theatrical weapon. The kukri is a kukri sword, machete, and lifeline all in one—an instrument of death, yes, but also of discipline and devotion. Gurkhas use it not just in combat but in ceremony, in daily labor, and in rituals of protection.

Unlike the sterile symmetry of Western blades, the kukri curves. It bites into flesh not like a needle, but like inevitability. In my view, the kukri embodies a Nietzschean philosophy: it is the will to power in steel form.

Birth of the 2nd Battalion: The Assam Sebundy Corps (1835)

In 1835, the need for extended coverage of the northeastern frontier led to the formation of the Assam Sebundy Corps, later the 2nd Battalion of the 8th Gurkhas. This unit, under Captain William Simonds, was initially a ragtag composite of Assamese tribesmen, hill warriors, and Nepalese volunteers.

By the 1840s, both battalions had evolved into disciplined regiments trained for irregular mountain warfare. They fought without support, without spectacle. They were the steel nerves of the Empire’s rawest edges.

The Naga Expeditions: Learning to Bleed in Silence And Unheard Usage of Gurkha Kukri

Between 1839 and 1851, the 8th Gurkhas engaged in seven separate expeditions against the Nagas. These weren’t wars in the European sense—there were no lines, no flags, no surrender. The Nagas fought like the forest itself—ambushes, poison arrows, traps made of sharpened bamboo stakes (punjis), and stockades designed to kill and vanish.

The 8th didn’t just match them; they adapted. They moved in single-file patrols, learned to traverse jungle in darkness, and used the kukri machete in close-quarter jungle combat, where firearms became liabilities and silence was the only cover.

To fight the Nagas was to confront a version of yourself that had not yet been civilized. It demanded transformation—not just of tactics, but of soul.

The Lushais, the Hills, and a New Kind of War

By the 1840s, Lushai raiders began descending into the Surma Valley, pillaging villages and abducting locals. In 1849, under Colonel E.G. Lister, the 8th Gurkhas were sent into the Lushai Hills. What they uncovered was a network of tribal fortresses holding over 400 captives.

They burned villages, freed hostages, and killed without pause. And yet Lister had the wisdom of Watts, not just the brutality of Nietzsche. He proposed roads, permanent posts, and local policing levies—solutions that worked long after bullets stopped flying.

This was typical of the Gurkhas: not just soldiers, but practical agents of long-term peace. They earned their stripes not by breaking skulls alone, but by building what came after.

The Indian Mutiny (1857): The Test of Loyalty & Gurkha Kukri

When the Indian Mutiny broke out, the British feared widespread defection. But not from the 8th Gurkhas. When the 34th Native Infantry mutinied at Chittagong and headed toward Sylhet, it was the Gurkhas who met them at Latu, after a 100-mile forced march in four days.

Major Byng led the charge and was killed. His bugler, a man named Mahabulla Khan, shouted “You’ve only killed the sergeant-major!” and sounded the charge under gunfire.

An old pensioner, Subhan Khattri, took his kukri and tulwar, charging alone until death met him like an old friend. This is the kind of loyalty that no doctrine teaches. It’s the kind that’s born from lineage, from soil, from honour.

And no, they didn’t receive a battle honour. But I say: Medals are not the measure of meaning. Memory is.

France, Mesopotamia, and the World Stage

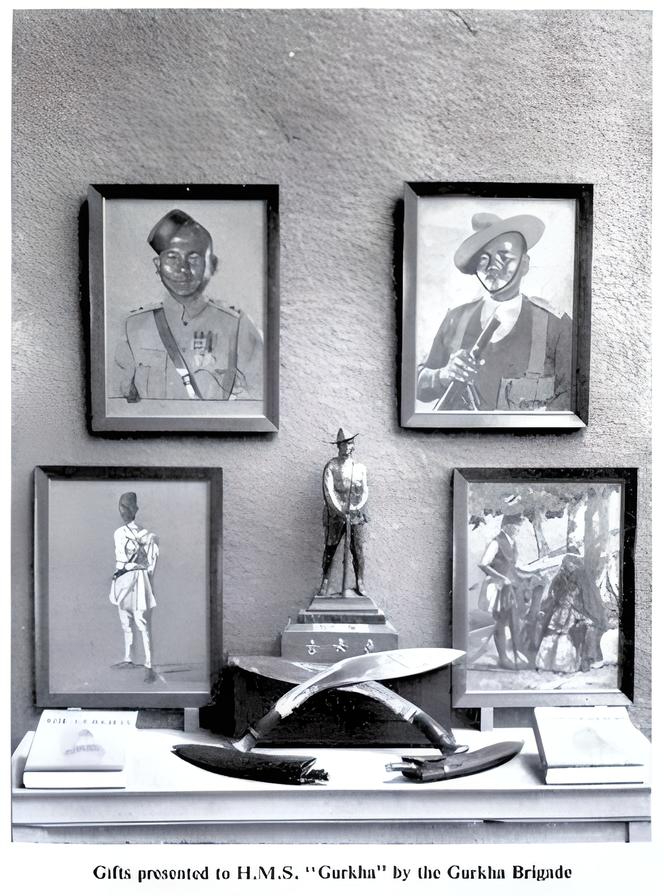

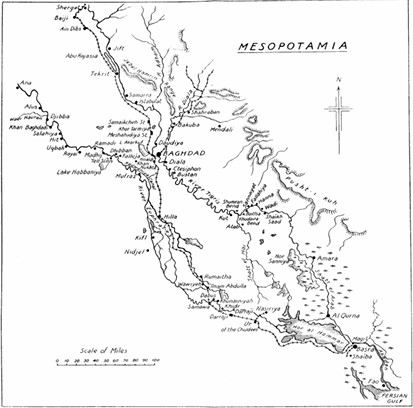

The 8th Gurkhas went on to fight in France (1914-15), facing machine guns and gas in the trenches of La Bassée and Neuve Chapelle. They were among the first Indian troops on European soil.

In Mesopotamia, they fought on the Tigris and helped liberate Baghdad. In Palestine, they charged at Megiddo. These were not footnotes—they were primary cogs in the war machines of both World Wars.

Their kukri was always there. Not a backup weapon, but the one that closed the distance when rifles jammed, when trenches were too tight, when men screamed, and the only answer was steel.

Second World War: From Burma to Italy Gurkha Kukri

During WWII, the Regiment served in:

- Burma (Arakan, Imphal, Irrawaddy)

- Italy (Gothic Line, Senio River)

- North Africa (1942)

- Java (1946)

At Imphal, they held their ground under Japanese onslaught. In Italy, they moved through the Gothic Line like ghosts, clearing hilltop bunkers and defusing mines with sheer resolve.

Each man carried a kukri, sharpened daily. Not for show—but for readiness. The kukri was never sheathed without drawing blood, as tradition dictates.

Even today, at Himalayan Blades, this principle continues—not in violence, but in respect for legacy. Himalayan Blades Imports steel from India.

Post-Independence: Service to India (1947–49)

In 1947, when India gained independence, the 8th Gurkhas chose to remain in Indian service. The British officers departed. But the soul of the Regiment—its loyalty, its kukri, its training—remained unbroken.

The final entry in their British chapter ended in 1949, but their Indian chapter continues today in the 8 Gorkha Rifles, still revered, still feared.

The Kukri Today: More Than a Blade

Today, the Gurkha kukri has become a global symbol—featured in survival kits, martial arts schools, and military museums. Yet the versions most people handle are imitations of steel and not of soul.

At Himalayan Imports and with forges like Himalayan Blades, you can still acquire a true kukri machete—hand-forged, full-tang, treated by quenching and tempering, designed not for shelves but for survival. Learn about the anatomy of fullers in Kukri.

A real kukri is not a fashion. It is an heirloom. It demands your respect. Because behind every authentic kukri lies a century of war, of peace, of silence.

Own your kukri, a piece from the history, accurately reproduced at himalayan blades.

Conclusion: Legacy as Law

If history is written by victors, then silence is written by those who bled without applause. The 8th Gurkha Rifles fought for over a century—not just across continents, but across ideals.

In their story lives the legacy of the kukri knife—a blade that does not forget. A blade that does not apologize. A blade that, like Nietzsche’s Ubermensch, cuts through illusion toward truth.

And in an age of digital noise, this silence… is worth listening to.

FAQs: The 8th Gurkhas and the Kukri

Q1. What is the difference between a kukri knife and a kukri sword?

The term kukri knife typically refers to utility or military models, while kukri sword may refer to longer ceremonial versions. All kukris share the distinct curved blade and are traditionally used by Gurkhas.

Q2. Did the 8th Gurkha Rifles always use the kukri?

Yes. From the early 19th century to modern times, the kukri has been an inseparable part of the Gurkha identity, both in battle and in tradition.

Q3. What are Himalayan Imports or Himalayan Blades?

They are modern forges and distributors of authentic Gurkha blades. They preserve the tradition of hand-forging kukris using time-honored metallurgy techniques.

Q4. Are kukri machetes practical for survival or just ceremonial?

A real kukri machete is both: a survival tool and a warrior’s weapon. It’s excellent for clearing brush, chopping wood, and, if necessary, self-defense.

Q5. Is the 8th Gurkha Rifles regiment still active?

Yes. Now part of the Indian Army, the 8 Gorkha Rifles continues to serve with distinction and carries forward the traditions of the original regiment.