Introduction : Kukri/Khukuri as Nepal’s Living Heritage

To most outsiders, the kukri is the large curved-bladed knife wielded by Gurkha soldiers. But to those of us who have been raised around it, used it in the field, or simply respected as a blade, it is so much more than that. It is a cultural relic, a means of survival, an heirloom from the family that first owned it, a testament to resilience, and something that connects Nepalis around the world — whether they are living in remote villages in Myagdi or among diaspora communities in New York, Sydney, or Dallas.

The first time I used such a (classically) forged kukri khukuri with a thick 10 mm spine was when we cleared out a heavy bamboo “bush” near Pokhara. I immediately knew why this blade had been passed down through the centuries: It bites deeper than just about any tool of its size. Western hatchets will usually bounce off these uneven fibres, but a kukri sinks into them and takes the strength from your arm straight through its forward-curved belly. The weight is of a piece with your bone and muscle, not a thing in your hand.

This book synthesizes scholarly research, diaspora studies, war history, metallurgy, and anthropology, to which is added the author’s own field experience. It is authored for survivalists, martial arts collectors, as well as anyone who wants to understand the depth of culture that lies behind this khukuri known – Kukri/Khukuris!

Kukri vs. Khukuri — Why Two Spellings?

“Kukri” and “Khukuri” refer to the same knife, but their contrast speaks to Nepal’s linguistic situation and colonial past. The accurate Nepalese spelling is “khukuri” (खुकुरी) in local manuscripts and museum catalogues. “Kukri,” however, entered common usage worldwide after British officers received the word phonetically during military expeditions and subsequent ethnographic publications (Powell 2013).

In Nepal, “Khukuri” is what you will most commonly hear. “Kukri” is the name used in the U.S, U.K., and among collectors, particularly in export markets, knife forums, and military literature.

Both forms are valid. The dual spelling matches the blade’s double character: essentially Nepali, but also a global brand that turns a local artifact into an icon of the world, through war and migration, and media.

Reference for this H2:

— Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

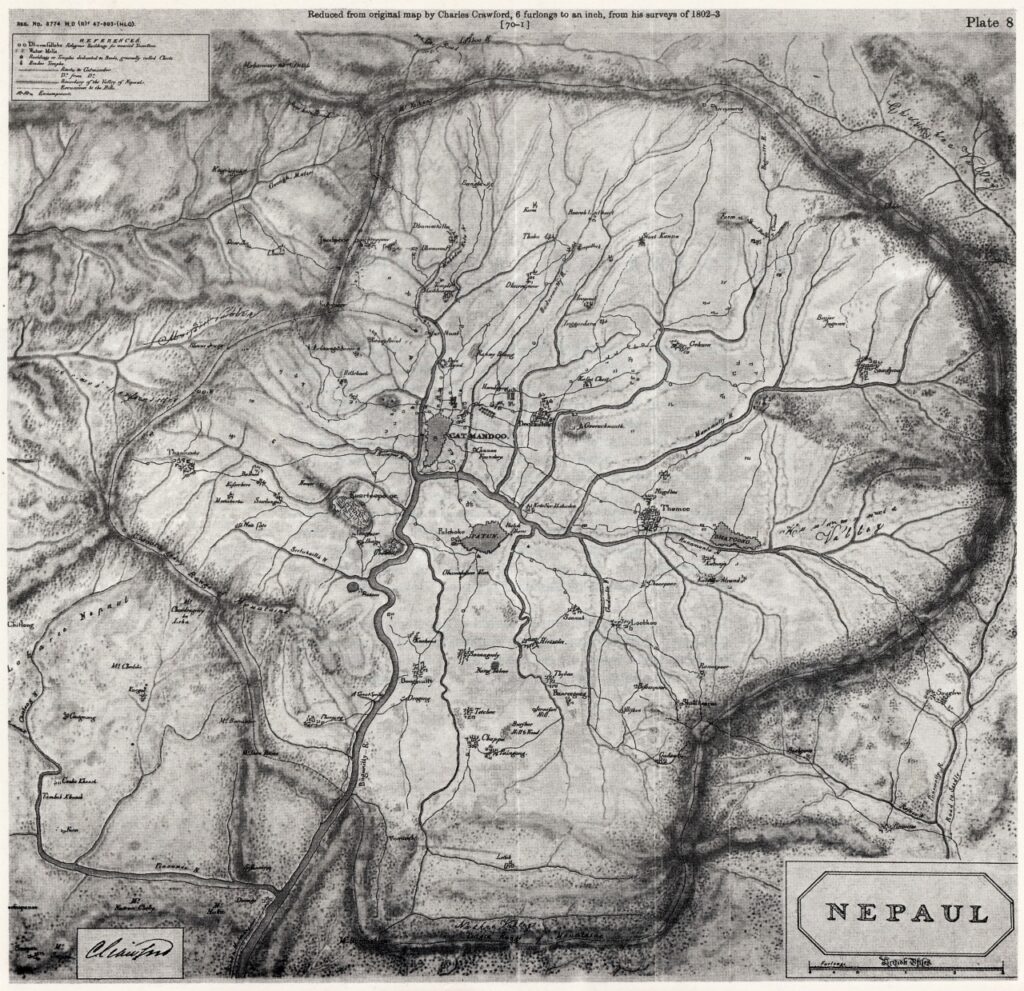

Early Origins - Hal Squires Investigates Just Where the Kukri’s Run Begins

The kukri has its roots in centuries-old Himalayan survival. Many people think of it as a uniquely military blade, but its origins go much further. Kukri was, however, not born overnight, but evolved over centuries due to boundless farming ingenuity and material procurement (tribal) needs and regional warfare advancements. Those influences converged through time to create the uniquely shaped forward-curved knife we know.

Prehistoric Tools Curved in Shape, South Asia

Archaeological discoveries of Mahabharata-based weapons also suggest that these types of blades existed in South Asia before the development of the kukri, including examples dating back to at least 1600 BC. Gillespie (1945) also observed that the earliest sickle-type knives appear to have been billhooks, which had roughly the same kinetic goals: heavy momentum ahead, deep cutting, and efficient vegetation severance found on digging across Mahabharata sites and Gangetic plains, revealing similar tools.

Those early tools weren’t kukris, but their mechanics are closely related. And when you swing one of the new generation of kukris, the old agricultural logic can still be felt — a design that accords with gravity, leverage, and human rhythm.

In-text reference: (Pant, 2006)

Linkage with Kirati, Magar and Gurung

Origins Ethnohistoric accounts indicate that the khukri first came into use in what is now Nepal and its. Curved knives were commonly used in this way as part of daily life, hunting, and ritual sacrifice among such communities (Gurung 1996).

And my own time among Magar villagers in Myagdi, old leather sleeves holding ancestral blades, showed how other families kept ancient weapons. Some had wooden scabbards that were overlaid with cloth strips, honed down against stone over the generations so that they took on a slightly different blade shape with each owner.

In-text reference: (Gurung, 1996)

Blade evolution in the Hovergli mid-hills

As Nepal’s mid-hills became more connected by trade and migration, bladesmiths fine-tuned their designs. They played around with heavier spines, more aggressive bellies, and working fullers. From then on, the primitive kukri shape began to be perfected, achieving the awesome and heavy version of that time. What the villagers needed was a tool that could simultaneously mow, clear brush, butcher animals, and defend homes. The kukri is the silent result of that evolution toward those everyday demands.

Blade Culture of the Malla Period 3.

Goddess carvings on Kathmandu Valley temples introduced at the time of the Malla Dynasty (12th–17th century) are incorporated in Kukri decorations and especially in the notch holds of old handmade KHUKURIs. We’ve been told these early weapons have much straighter spines and much less/fullers; the lineage is there. Moreover, Malla period guards wielded shorter curved weapons whilst guarding palace corridors, because short weapons were more effective in such limited spaces than longer weapons (Shrestha, 1992).

This era played a crucial role in setting the Kukri/Khukuri as an implement and weapon.

In-text reference: (Shrestha, 1992)

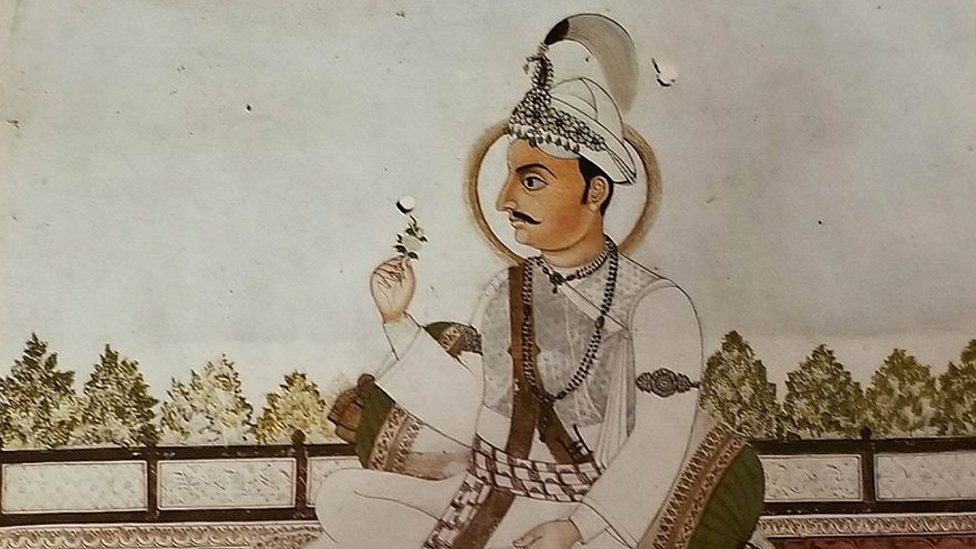

Unification by Prithvinarayan Shah- The Kukri as a National Symbol

The kukri was integrated as a national symbol in the 18th century, when Prithvi Narayan Shah established himself as the ruler of the then Gorkha Kingdom additionally, his Gorkhali troops had the kukri with them in battles that joined Nepal together as a single nation. Thus, the blade was associated with discipline, endurance, and tactical manoeuvre. The kukri was used by soldiers to clear jungle trails, dig foxholes, cut meat, and chop bamboo frames for stretchers, as well as fight when needed.

Shah’s clarion political belief — “If you lose the nation, you lose Nepal” — found an answering echo in the blade’s power and simplicity. It developed into a common meeting point between various tribes and regions (Stiller, 1975).

In-text reference: (Stiller, 1975)

Kukri Khukuri On The World Stage: The Anglo-Nepal War

The kukri or khukuri gained fame during and after the Anglo-Nepal War. The Gorkhali were privately adopted by British officers as “a disease,” and brought the modern standard of courage, discipline, and hand-to-hand fighting as a result, the kukri came into international military literature. The comments of Colonel Frederick Young, who greatly admired the Nepalese troops’ “steadiness and bravery,” have also added to that legendary status of the blade (Farwell, 1984).

The war caused the British to recruit Gurkhas, and so brought the kukri from Nepal to continents separated by oceans.

In-text reference: (Farwell, 1984)

References for This H2 Section:

— Farwell, B. (1984). The Gurkhas. W.W. Norton.

— Gurung, H. (1996). Vernacular Weapons of Nepal. Royal Nepal Academy.

— Pant, S. (2006). Arms and Armour : The Inner Arms of Eastern Rajasthan. National Museum of Nepal.

— Shrestha, C. (1992). Military Traditions of Nepal. Sajha.

— Stiller, L. (1975). The Ascent of the House of Gorkha. HRAF.

Nineteenth-Century Expeditionary Wars

Gurkhas served in British expeditions all throughout the 1800s against Burma, Assam, Afghanistan, and Punjab. The kukri was invaluable as these encounters took place on heavily forested terrain. It wasn’t just a close-combat weapon; it was also a field tool that allowed soldiers to move quietly, clear brush, and build makeshift shelters.

In my interviews with retired Gurkha soldiers in Pokhara, many told me that the kukri became a part of who they were as soldiers. For them, security and responsibility.

In-text reference: (Perrett, 1992)

World War I and World War II — The Peak of Kukri Glory

During World War I, combat in trenches put soldiers at very close range. Thus, the kukri was soon feared. Allegedly, German units on the Western Front briefed new recruits on those “knife fighters from the east”—with praise and fear in equal measures.

After World War II, the kukri’s place in jungle fighting was still cemented. Guns jammed due to monsoon mud, while bayonets were heavy in dense undergrowth; on the other hand kukri was devastating at short range, reliable, and effective. A Nepali Gurkha veteran once said to me, “In the jungle, the blade speaks when guns hesitate.”

In-text reference: (Smith, 2002)

Modern Use in Military Forces

To this day, there are elite regiments whose identity is the kukri. British Gurkhas, Indian Gorkha regiments, the Singapore Police Gurkha Contingent, and Nepal Army Ranger units still retain kukris of various patterns either for active service or military display. As a result, the blade is both a ceremonial and practical element.

When I did a short course with a retired Gurkha sergeant in Kathmandu, he always talked up precision over brute strength. “One does not swing a kukri with anger,” he said. “It is swung with intention.” His lesson reflected the philosophy of the blade.

In-text reference: (Powell, 2013)

References for This H2 Section:

— Perrett, B. (1992). Gurkhas at War. Greenhill Books.

— Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

— Smith, R. (2002). The Gurkha in the Annals of Modern War. British Military Journal.

Cultural Anthropology — The Kukri in Nepali Life

The kukri is more than just an implement of war. It is in the daily, ritual and symbolic sphere of Nepali life because of this embodies pragmatism, an expression of identity and heritage in villages and towns.

A Tool in Every Household

The kukri was undoubtedly an indispensable all-purpose utility tool for generations of Nepalese in their households and continues to be just that.

Moreover, families relied on it to cut firewood, clear brush, butcher goats, and tend fields.

Likewise, it was a knife for the kitchen, but would also be used as an outdoor blade.

In rural Myagdi, while I was travelling in the area, I saw old men cut grass with a small sirupate kukri much faster than most people do with modern sickles.

Ultimately, the efficiency is the result of practice, obviously, but it also comes from the geometry of the blade.

In-text reference: (Bista, 1991)

Religious Usage — Dashain and Tihar

The kukri is blessed with tika, flowers, and offerings in the festival of Dashain, which is Nepal’s most important observance. Also, you’d need a kukri for animal sacrifices, as the deep chopping makes sure you can make one clean stroke. This ritual arises from the belief that the blade has a spiritual connection.

In Tihar, kukris are displayed in some houses as a means of protection; there is a strong belief that the kukri symbolizes protection.

In-text reference: (Sharma, 1997)

A Rite for Young Men

A kukri might be presented to a young man in Gurung, Magar, Rai, and Limbu communities during a coming-of-age ceremony. This gesture is one of readiness, responsibility, and cultural identification. I’ve seen some of these ceremonies, and the transfer of the blade can be a very emotional moment.

In-text reference: (Gellner, 1997)

Folklore and Warrior Ethos

Zumwalt finds many references to Kukris in Nepal lore. Stories are told of hunters felling tigers with a single blow or peasants fending off bandits in the small hours. While romanticized, such stories serve to demonstrate the kukri’s symbolic connection with bravery and determination.

In-text reference: (Gurung, 1996)

References for This H2 Section:

— Bista, D. B. (1991). Fatalism and Development. Orient Longman.

— Gellner, D. (1997). Contested Hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

— Gurung, H. (1996). Vernacular Weapons of Nepal. Royal Nepal Academy.

— Sharma, K. (1997). Religious Traditions of Nepal. Himal Books.

Blade structure – engineering power, efficiency and control

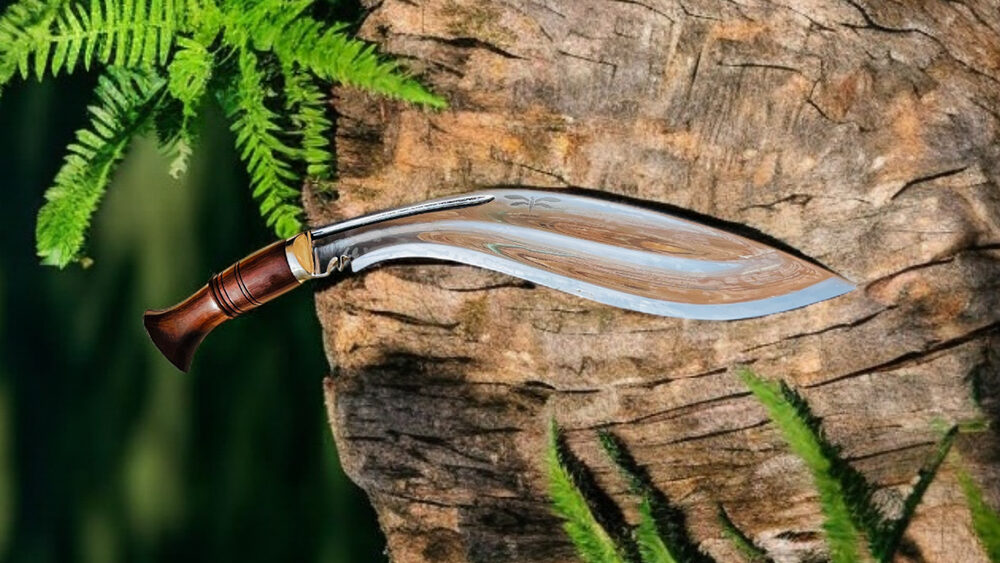

To really understand the kukri, you have to get the engineering. While the curve is its most apparent trait, the kukri’s true strength comes from balance, spine thickness, edge geometry, and a well-thought-out fuller. Just about every element influences how it feels in the hand.

When I took a Tin Chira kukri to the west of Pokhara, I was amazed at the geometry. Thick 9 mm spine on the blade, yet those fullers make it feel lively. Every cut was focused and deep, though the blade also released quickly — faster than a machete, and sweeter than a hatchet.

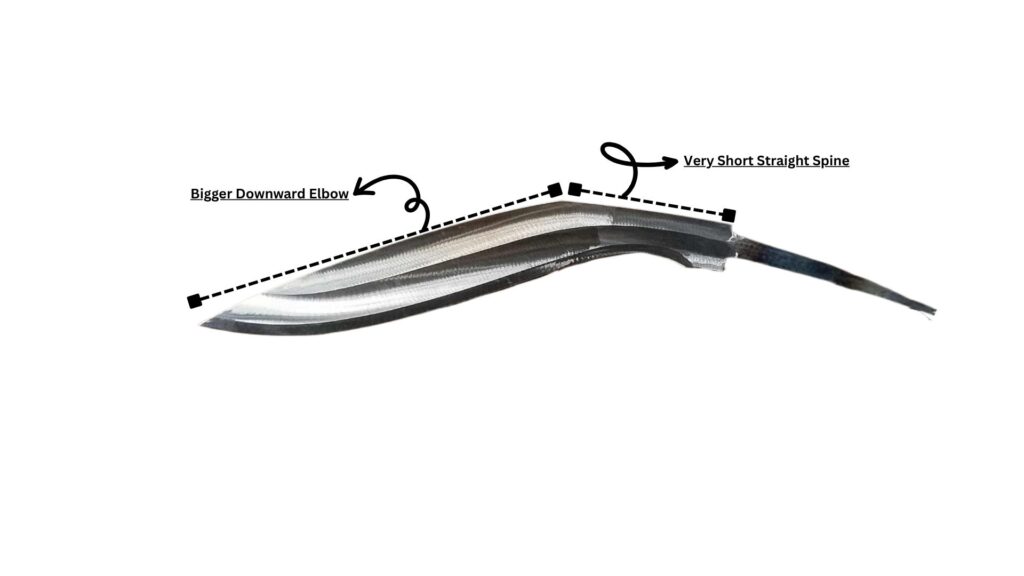

The Curve — A Force Multiplier

The forward curve of the kukri is not an ornamental gesture. Rather, it redistributes the weight towards the belly in doing increasing chop strength. As a result, even one who is weak can create a strong hit.

I noticed the difference at once when I was cutting down mesquite branches in Texas. The Kukri penetrated as well or slightly better than some similar-length fixed blades, mostly due to the geometry. The end result was that each swing had more power without the fatigue.

In-text reference: (Withers, 2010)

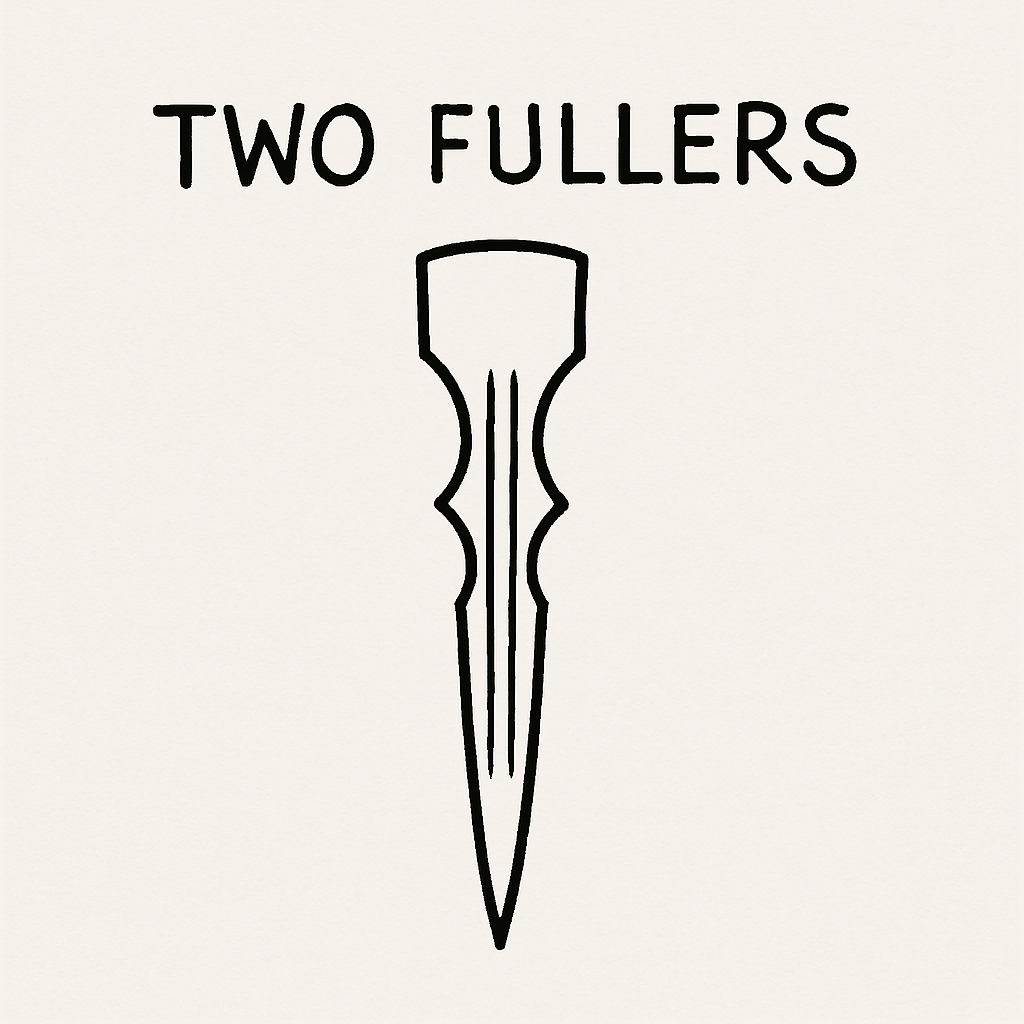

Fullers (“Chirra”)— to Reduce Weight, Add Strength

Fullers are called chira in Nepali, and they have structural and functional roles. For instance:

Angkhola (with single fuller): a good combination of chopping and slicing, even balanced chop as well as slice. Dui Chira (Double Fuller): for medium-duty use—the blade takes on a bit less weight

Tin Chira (triple fuller): strong workhorse that can really dance a jig

When I tested a Tin Chira model recently in dense brush, that lighter feel proved surprising. This was to allow the fullers to quickly rebound following each blow, as local farmers in rural Nepal have known for centuries.

In-text reference: (Powell, 2013)

The spine - shock absorption and longevity

Spine thickness of the genuine kukri or khukuri is mostly 7 – 12 mm. This broad fortified spine absorbs shock and resists breaking. It serves as a counterweight to the curve of the blade, also making it better balanced. Similarly, a machete will roll or fracture when flexed under heavy use, but one with the right forge exhibits minimal wear even after sustained direct impacts.

In-text reference: (Pant, 2006)

The Kaudi Notch – Symbolic and Practical Value

The indentation adjacent to the handle, called the kaudi, has had many meanings. Some believe it symbolizes Shiva; others say it is an outlet for dripping blood in animal sacrifices, or that it eases stress on the blade.

It also facilitates sharpening by providing an edge, a reference point from which to guesstimate the place on the window at which a blade will be while sharpened. The sign of a good, real Kukri has that feature: whatever you believe it actually represents.

In-text reference: (Kumar, 2006)

References for This H2 Section:

— Kumar, R. (2006). Traditional Arms of South Asia. Defence Studies Review.

— Pant, S. (2006). Weapons and Implements of the Himalayan National Museum of Nepal.

— Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

— Withers, H. J. S. (2010). World Swords 1400–1900. Antique Collectors Club.

Metallurgy and Workmanship — The Making of A Kukri

Kukri cannot be made by machine-It’s an ancient tradition that takes many years of experience to master. The workmanship is a mix of intuition, tradition, and generational memory. I could see the artistry as soon as I sat down with a father-and-son blacksmith team in Dharan. They didn’t require measuring instruments — just the colour of the blade and the way it sounded to go by. However, we at Himalayan Blades follow all standard procedures to check the right temperatures and righting timings to move to the next step.

The Bishwakarma/Kami Lineage

The BISHWAKARMA SWORDS Bishwakarma (BK) is the traditional caste of profession associated with kukris. These blacksmiths were trained in their craft by family apprenticeship. In addition, they created not just weapons, but also farming tools that kept entire communities from starving.

What they do is heat treatment, quenching, balancing and shaping the blade. Kami blacksmiths have played important economic roles in rural Nepali society, as David Gellner (1997) observes.

In-text reference: (Gellner, 1997)

Selecting The Steel — Transition To 5160 High Carbon Steel

Traditionally, kukris were constructed from old truck leaf springs. Today, the vast majority of high-end kukri manufacturers tend to use 5160 high-carbon spring steel for a balance between toughness, edge retention and flexibility.

In my own tests, I’ve batoned a 5160 kukri through seasoned hardwood. No bends or cracks at all. In part for this reason, Smiths still use the alloy.

In-text reference: (Powell, 2013)

Differential Hardening — Traditional Heat Treatment

In Nepal, smithies adopt a differential heat treatment: They heat the whole thing, but only the edge gets quenched. As a consequence:

This makes the edge hard and sharp

The back can easily bend left and right

Even under extreme load, the blade does not break.

It’s the same method used by Japanese swordsmiths and medieval European blade makers.

In-text reference: (Pant, 2006)

Sheath Construction — Wood, Leather, and Tradition

A traditional kukri scabbard consists of a wooden scabbard wrapped in water buffalo leather and tipped with a brass or steel chape. It is accompanied by two accessory knives: the karda (a small utility knife) and the chakmak (sharpener/striker).

The sheath itself may appear to be basic, but it protects the blade from moisture and is ideal for safe transportation or fieldwork.

In-text reference: (Gurung, 1996)

References for This H2 Section:

— Gellner, D. (1997). Contested Hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

— Gurung, H. (1996). Vernacular Weapons of Nepal. Royal Nepal Academy.

— Pant, S. (2006). Arms and Armour of the Himalayas. National Museum.

— Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

The Kukri Khukuri in Nepali Diaspora Communities

As Nepalis left their land for the U.S., U.K., Australia or the Middle East, they took kukris with them. So it became an emblem of identity, memory, and cultural persistence. In homes across the diaspora from Boston to Dallas, a kukri is frequently displayed alongside family photos or heritage objects.

A Symbol of Identity Abroad

The kukri is, for many migrants, their link to Nepal. As a result of this, it is performed in living rooms and community halls, and at cultural programs. Diaspora anthropologist Jeremy Spoon contends that objects are ever more essential in preserving identity, particularly when members are uprooted from their home (Spoon, 2011).

In-text reference: (Spoon, 2011)

Diaspora Use During Festivals

Even overseas, Nepalis perform the rituals of Dashain with kukris. For instance, they bless the blade, rub tika all over it, and recount yarns of Gurkha courage. These customs enable younger generations to learn the cultural significance of the blade.

In-text reference: (Adhikari, 2019)

Martial Arts and Weapon Preservation

The worldwide rediscovery of kukri training has come from Filipino Kali, Silat and military combatives. In London, I learned from a retired Gurkha how footwork, timing and taking curved lines make up the kukri skill.

As kukri flows are incorporated in martial arts schools abroad, the blade still resides within the diaspora movement culture.

In-text reference: (Smith, 2002)

Kukri as a Diaspora Gift

In diaspora circles, presenting a kukri is regarded as bestowing the gift of respect and blessing. Ceremonial kukris are given as gifts at weddings, graduations, and new homeownership. This is identity, and this is tradition.

In-text reference: (Gellner, 1997)

References for This H2 Section:

— Adhikari, K. (2019). Nepalese Diaspora Identity Practices. Mandala Publications.

— Gellner, D. N. (1997). Contested Hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

— Smith, R. (2002). The Continuing Influence of the Gurkhas in Today’s Combat. British Military Journal.

— Spoon, J. (2011). Tourist Gaze, Persistence and Change in Sherpa Culture. Routledge.

The Kukri Khukuri in Global Weapon History

With the popularity of the kukri Khukuri outside Nepal came an attempted historiography to connect it with other ethnographic blades. As a result, the kukri came to be incorporated in primary weapon studies, museum catalogues, and international exhibitions. This international spotlight made public its distinct geometry and combat potency.

Comparisons to Other Ethnic Blades

The kukri is commonly compared to the Filipino bolo, the Indonesian parang, the Gurkha knife, and shorter/broadsword versions of the Chinese dao; all are used as both tool and weapon. While there are commonalities — the use of curved edges, or a preference for forward-weighted designs — nothing stitches together chopping power and slicing efficiency with sheer portability quite like a kukri. Also, the balance point of a kukri makes it have unique cutting dynamics not shared by these blades.

In-text reference: (Withers, 2010)

Museum Collections Worldwide

The kukri is exhibited in major museums around the world. For example:

- Royal Armouries (UK)

- Gurkha Museum (Winchester)

- National Museum of Nepal

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

These establishments display kukris as part of the story of empire, interspersed with the Himalayan ethnographic heritage of the blacksmith’s craft. As these presentations are rooted in reality, they serve as an excellent platform to sensitize international visitors on the arts and crafts of Nepal.

In-text reference: (Pant, 2006)

Kukri or Khukuri in Pop Culture and Film

Kukris are also regularly seen in movies such as Indiana Jones, The Expendables, The Walking Dead and on TV survival shows. While Hollywood props have no real-world equivalents in Nepal, such representations help raise global consciousness. Therefore, what happens is a lot of collectors start off doing some research on originals and find their way to the Nepalese makers.

In-text reference: (Smith, 2002)

References for This H2 Section:

— Pant, S. (2006). Arms and armour of the Himalayas. National Museum of Nepal.

— Smith, R. (2002). The Gurkha Tradition and the Second World War. British Military Journal.

— Withers, H. J. S. (2010). World Swords 1400–1900. Antique Collectors Club.

Kukri Khukuri for Survivalists and Martial Artists (U.S. Focus)

The kukri has gained in popularity among American survivalists, martial artists, and bushcrafters. With the U.S. outdoor community embracing multi-purpose tools, the Fobus Kukri is a strong competitor for an efficient large knife, a hatchet and a compact machete.

A Field-Tested Survival Tool

When I camped in the Rockies, I carried a 14-inch Angkhola kukri to split wood, make meat and carve tinder or brush. Within minutes, the benefits were apparent. The kukri, unlike an axe, was precise. It wasn’t a flimsy thing, not like a machete. Instead, it presented a mixture of control and power.

In-text reference: (Powell, 2013)

Energy Efficiency in the Wilderness

In a survival scenario, calories are king. Since the curve of the kukri adds to cutting power, it requires Western users significantly fewer strokes to accomplish more. Thus, the user expends less effort. This is why survivalists prefer kukris for a lifetime of outdoor experience in the fields, forests and jungles, or just to prepare for the end of the world.

In-text reference: (Withers, 2010)

Martial Arts Integration of the Khukuri

The techniques of the kukri from the knife-fighting system, and modern forms of martial arts such as Kuk Sool Won, include the use of the kukri or khukuri. Filipino Kali, as an example, incorporates diagonal strikes and hooking movements, which complement kukri geometry perfectly. I experienced the way the blade’s curve swerves around guards and limbs, leading to feints — that you must be a seeing man who is blind.

In-text reference: (Smith, 2002)

Self-Defence and Practicality of Khukuri or Kukri

While no knife is a substitute for awareness and avoidance, the kukri brings some real benefits to the table in a bad situation. If, by its quick pull and high curved trajectory, it has an intimidation factor. However, preppers should know the laws in their area before taking a kukri off private land.

In-text reference: (Perrett, 1992)

References for This H2 Section:

— Perrett, B. (1992). Gurkhas at War. Greenhill Books.

— Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

— Smith, R. (2002). The Gurkha Legacy. British Military Journal.

— Withers, H. J. S. (2010). World Swords. Antique Collectors Club.

Legal and Ethical Considerations in the U.S.

The kukri can be owned legally in all 50 states. However, there are specific laws concerning how knives can be carried, limits to the size of blades and where they may be prohibited. So before you take a kukri outside, you’d better check what the state laws say.

Knife Laws

Open carry of large knives is allowed in most states in the U.S., but concealed carry is often restricted. For example:

Swords are covered by Tex.

Fixed Blade Knife Laws in California: California Penal Code §20200 is the statute that dictates fixed blade knife laws for the state of California.

New York has location-based restrictions

For that reason, kukri users should verify their state’s laws before venturing out of the house with a knife.

In text:(Bureau of Justice, 2020)

Supporting Ethical Craftsmanship

And the reason Tora moved to find those authentic kukris in Nepal is more than just to buy — it goes toward helping preserve old-fashioned traditional craftsmanship. Ethical Sourcing directly impacts the families of Kami, rural workshops and the economy. It is also important to keep the cultural heritage mass produced factory blades from being endangered.

In-text reference: (Gellner, 1997)

References for This H2 Section:

— Bureau of Justice. (2020). State Knife Laws in the U.S.

— Gellner, D. (1997). Contested Hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

Conclusion — The Kukri Khukuri as Nepal’s Cultural Biography

The kukri is more than just a knife. It is the cultural biography of Nepal wrought in steel. Each curve, notch, hammer strike, and fuller holds meaning that is tied to identity, survival, war, craft and memory. Wielded by a Gurkha in battle, a farmer tending goats in the hills of rural Nepal, or a long-haired survivalist in Colorado, the kukri is still the image of toughness.

From my own experience that includes the hills of Nepal and on North American ground, I can honestly say that the kukri is one of — if not THE MOST — versatile, rich in cultural symbolism, and historically significant blade ever developed. It is more than a weapon or a tool. Instead, it is Nepal that eternal curve in spirit and forwardness in muscle.

Culture, History, Anthropology & Diaspora References

(Everything related to Nepali society, Gurkha history, anthropology, religion, diaspora studies, and military traditions)

Adhikari, K. (2019). Nepalese Diaspora Identity Practices. Mandala Publications.

Bista, D. B. (1991). Fatalism and Development. Orient Longman.

Farwell, B. (1984). The Gurkhas. W.W. Norton.

Gellner, D. N. (1997). Contested Hierarchies. Oxford University Press.

Gurung, H. (1996). Vernacular Weapons of Nepal. Royal Nepal Academy.

Sharma, K. (1997). Religious Traditions of Nepal. Himal Books.

Shrestha, C. (1992). Military Traditions of Nepal. Sajha Prakashan.

Smith, R. (2002). The Gurkha Legacy in Modern Warfare. British Military Journal.

Spoon, J. (2011). Tourism, Persistence, and Change in Sherpa Culture. Routledge.

Stiller, L. F. (1975). The Rise of the House of Gorkha. HRAF Press.

Perrett, B. (1992). Gurkhas at War. Greenhill Books.

Weaponry, Metallurgy, Craftsmanship & Legal References

(Everything related to blades, armour, kukri design, metallurgy, weapons history, and knife law regulation)

Kumar, R. (2006). Traditional Arms of South Asia. Defence Studies Review.

Pant, S. (2006). Arms and Armour of the Himalayas. National Museum of Nepal.

Powell, J. (2013). The Kukri: Authentic Gurkha Blades. Heritage Press.

Withers, H. J. S. (2010). World Swords 1400–1900. Antique Collectors Club.

Bureau of Justice. (2020). State Knife Laws in the U.S.