Kukri Tang Explained: A Research Study on Tang Construction in Kukris

By Himalayan Blades

Forged knowledge from historical study, metallurgy, and workshop experience about the kukri tang.

Abstract

The kukri tang is the least visible yet most structurally critical component of any knife. In the kukri—an impact-driven, forward-weighted blade developed in the Himalayan region—the tang functions as the primary load-transmission system between blade and user. Despite this, modern discourse surrounding kukri tang construction is dominated by misconceptions, oversimplified marketing claims, and the inappropriate application of Western knife standards.

This research article presents a comprehensive examination of kukri tang construction, integrating historical documentation, metallurgical principles, failure analysis, and real-world forging experience from Himalayan Blades. It explores traditional and modern kukri tang types, compares them with other knife tang systems, evaluates full tang kukri designs critically, and explains why authentic Gurkha kukris relied on forged tapered tangs rather than exposed steel. The study is intended for survivalists, martial artists, self-defense practitioners, and blade enthusiasts—particularly within the US market—who value structural truth over cosmetic strength by Himalayan Blades.

1. Introduction: Why the Tang Defines the Kukri

The kukri is sometimes incorrectly thought to be just another curved knife. In reality, a kukri is a specialized blade system engineered around rotational force and forward-weighted geometry. Kukris are designed with pronounced curvature and heavy forward mass distribution. In contrast, a traditional straight knife is intended for linear slicing or thrusting; a kukri functions by swinging through angular motion to generate power.

The blade of a kukri moves in a downward, forward arc, allowing momentum to drive impact more efficiently. This mechanism reduces the physical effort required from the user while increasing cutting effectiveness. Because of this design, kukris excel at chopping and demanding utility tasks rather than delicate slicing alone.

1.1 How Stress Travels Through a Kukri

The geometry of a kukri blade does not allow stress to distribute evenly during use. Contrary to common assumptions, most mechanical stress does not occur at the cutting edge or along the spine. Instead, stress concentrates at the junction where the blade transitions into the handle.

This blade-to-handle junction absorbs repeated shock, torsion, and vibration from chopping, batoning, and impact work. As a result, this portion of the tang becomes the primary load-bearing structure of the entire kukri.

1.2 Why Tang Design Determines Structural Survival

In practice, the tang design determines whether a kukri survives long-term use. A kukri can be expertly forged, properly balanced, and extremely sharp, yet still fail catastrophically if the tang’s geometry, steel composition, or heat treatment is inadequate.

When tangs are poorly shaped, improperly welded, or inconsistently hardened, stress accumulates faster than the steel can dissipate it. This leads to fractures that may appear sudden, but are mechanically predictable failures.

1.3 Experience-Based Understanding from Himalayan Blades

Understanding tang construction goes beyond theory—it requires direct experience. At Himalayan Blades, this knowledge comes from hands-on analysis rather than assumptions. We have examined kukris returned after prolonged heavy chopping, dissected export-grade blades fitted with welded tang extensions, and restored antique Gurkha kukris that have remained fully functional after more than a century of service.

Across all these cases, the same structural pattern emerges consistently, regardless of blade size, style, or era.

The conclusion is unavoidable: the tang determines whether a kukri becomes a lifelong tool or a short-lived object. It is the hidden structural core of the kukri—rarely visible, often overlooked, yet ultimately responsible for durability, safety, and long-term performance.

2. What Is a Tang? A Structural Definition

In engineering terms, a tang is a cantilevered structural member embedded within a composite system (handle material, adhesive, and grip). Its function is to transfer mechanical energy from the blade to the hand while resisting bending, torsion, and fatigue.

In most knives, axial loads dominate. In kukris, however, bending moments and torsional loads dominate, because the blade’s center of mass lies forward of the grip. Every chop generates a bending impulse that peaks at the tang shoulder.

This is why the kukri tang design cannot be evaluated using the same criteria as:

- Chef knives

- Daggers

- Straight survival knives

Applying those standards blindly is one of the biggest sources of misinformation in modern kukri discussions.

Reference: Verhoeven, J.D., Steel Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist, ASM International.

3. Historical Origins of Kukri Tang Construction

3.1 Pre-19th Century Himalayan Kukris

Early kukris were forged in village smithies across Nepal and the Himalayan foothills using reclaimed iron and bloomery steel. Material quality was inconsistent; forging skill compensated. Surviving examples from this period display:

- Narrow, tapered tangs

- Asymmetrical cross-sections

- Deep handle insertion

- Resin or pitch-based fixation

Modern observers often misinterpret these features as “primitive.” In reality, they represent adaptive engineering. Tapered tangs reduce stress concentration and permit controlled elastic deformation under impact—preventing brittle fracture.

This same principle appears independently in Japanese sword nakago and early European falchions, demonstrating convergent evolution in blade engineering.

Reference: Rawson, P.S., The Indian Sword, Victoria & Albert Museum Publications.

3.2 Gurkha Military Kukris and British Documentation

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the British encountered kukris through Gurkha service. While blade dimensions and curvature were documented, no British ordnance specification mandated full tang construction.

Physical examination of authenticated Gurkha-issued kukris held at Fort William (Kolkata) and the Royal Armouries consistently shows enclosed forged tangs secured by resin and peening. These kukris endured jungle clearing, combat, and decades of daily use—clear empirical validation of traditional Gurkha knife tang construction.

Reference: Egerton, W., Indian and Oriental Arms and Armour.

Reference: Royal Armouries, Gurkha Kukri Collection Notes.

4. Kukri Tang Types: Accurate Classification

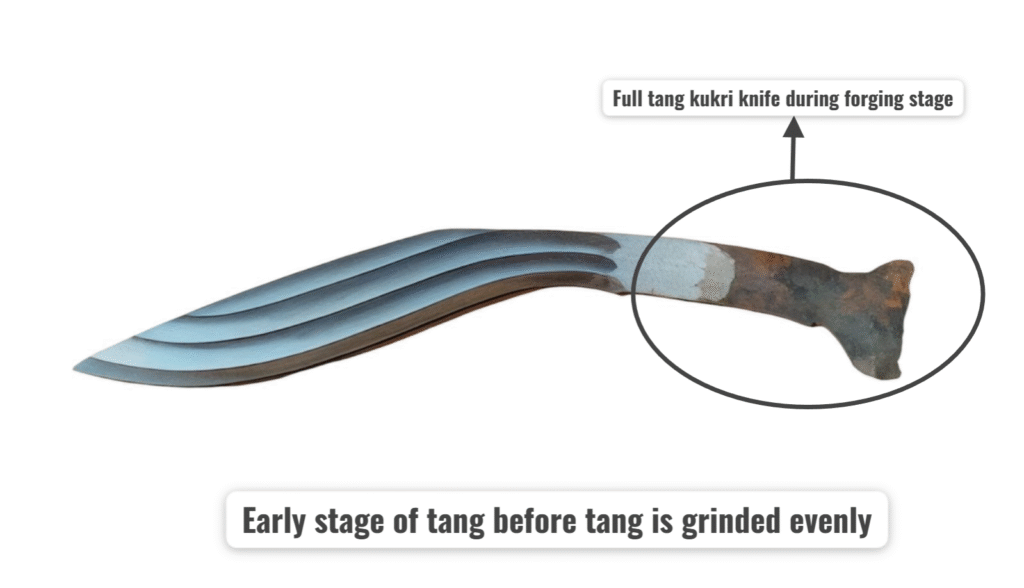

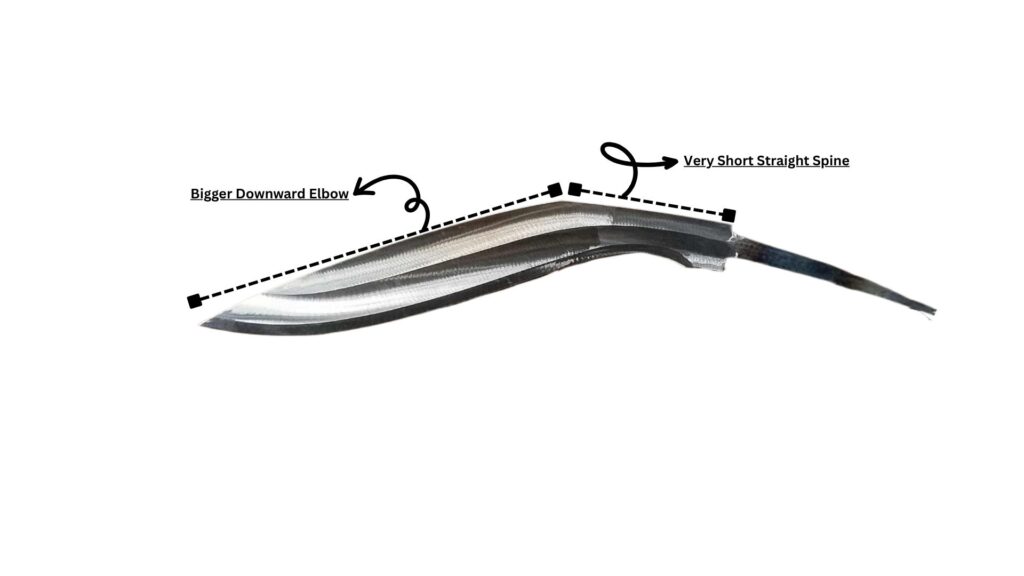

4.1 Traditional Forged Hidden Tang (Partial Tang)

This is the historically correct kukri knife tang.

Characteristics:

- Forged integrally from the blade

- Tapered in both width and thickness

- Continuous grain flow

- Deeply seated inside the handle, but does not exceed the handle material

The taper allows the tang to flex microscopically under load, dissipating energy gradually. When properly heat-treated, this design is exceptionally resistant to fatigue failure. The tang of the kukri knife and the handle material are fixed with adhesives. At Himalayan Blades, we use industrial glue and adhesives to fix it permanently. Indian Mutiny Officer Model, Hanshee Kukri, Royal Guard Hanshee Khukri are some of the models that have partial tangs.

Failures attributed to this tang type are almost always the result of poor forging, improper heat treatment, or inferior handle construction—not the design itself. I have done many chopping videos of partial tang kukris, and I have never encountered any failures related to the tang. Here is the link to the video when I performed the chopping test.

Reference: Verhoeven & Pendray, “Grain Flow and Forging Integrity,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology.

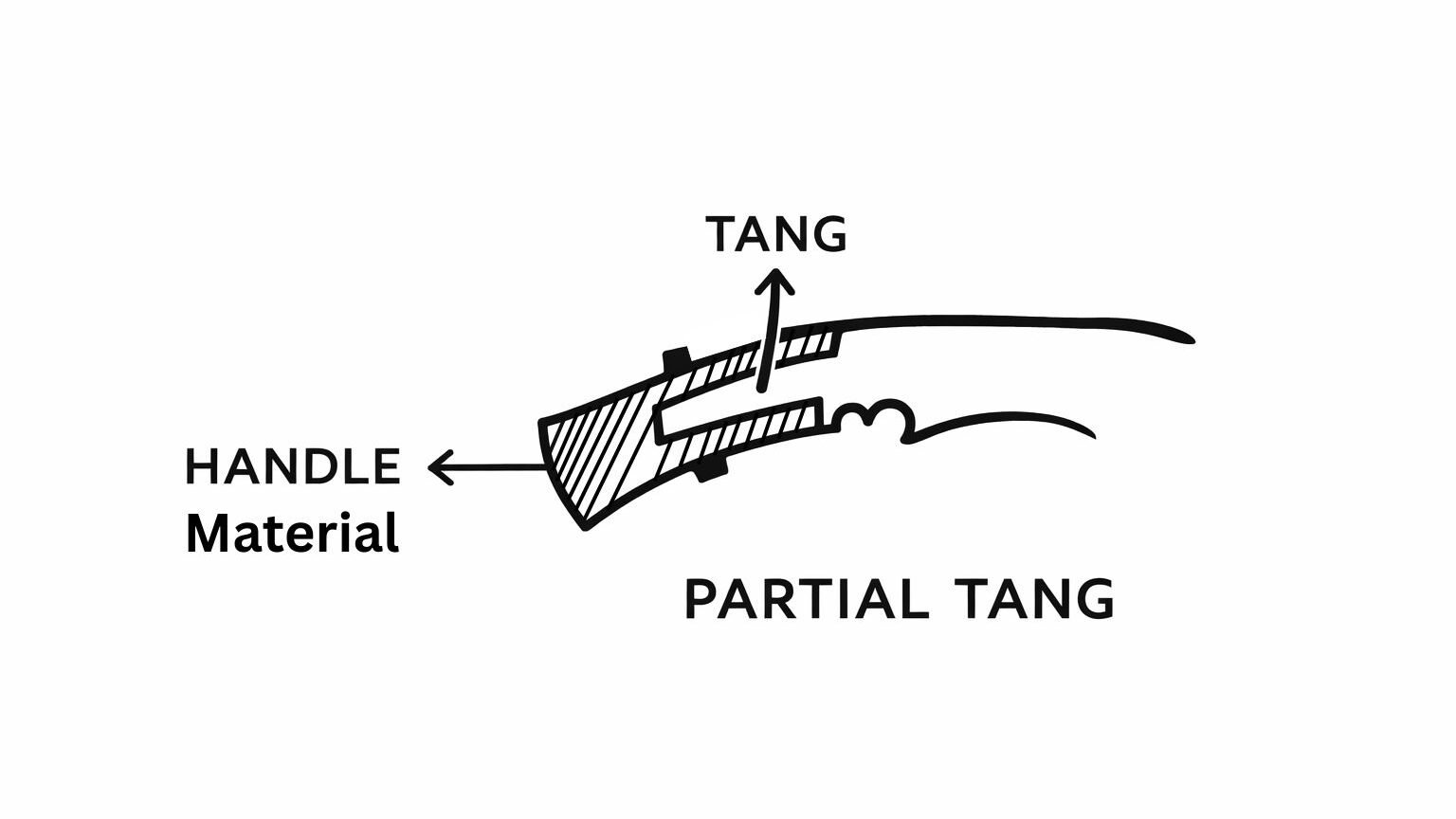

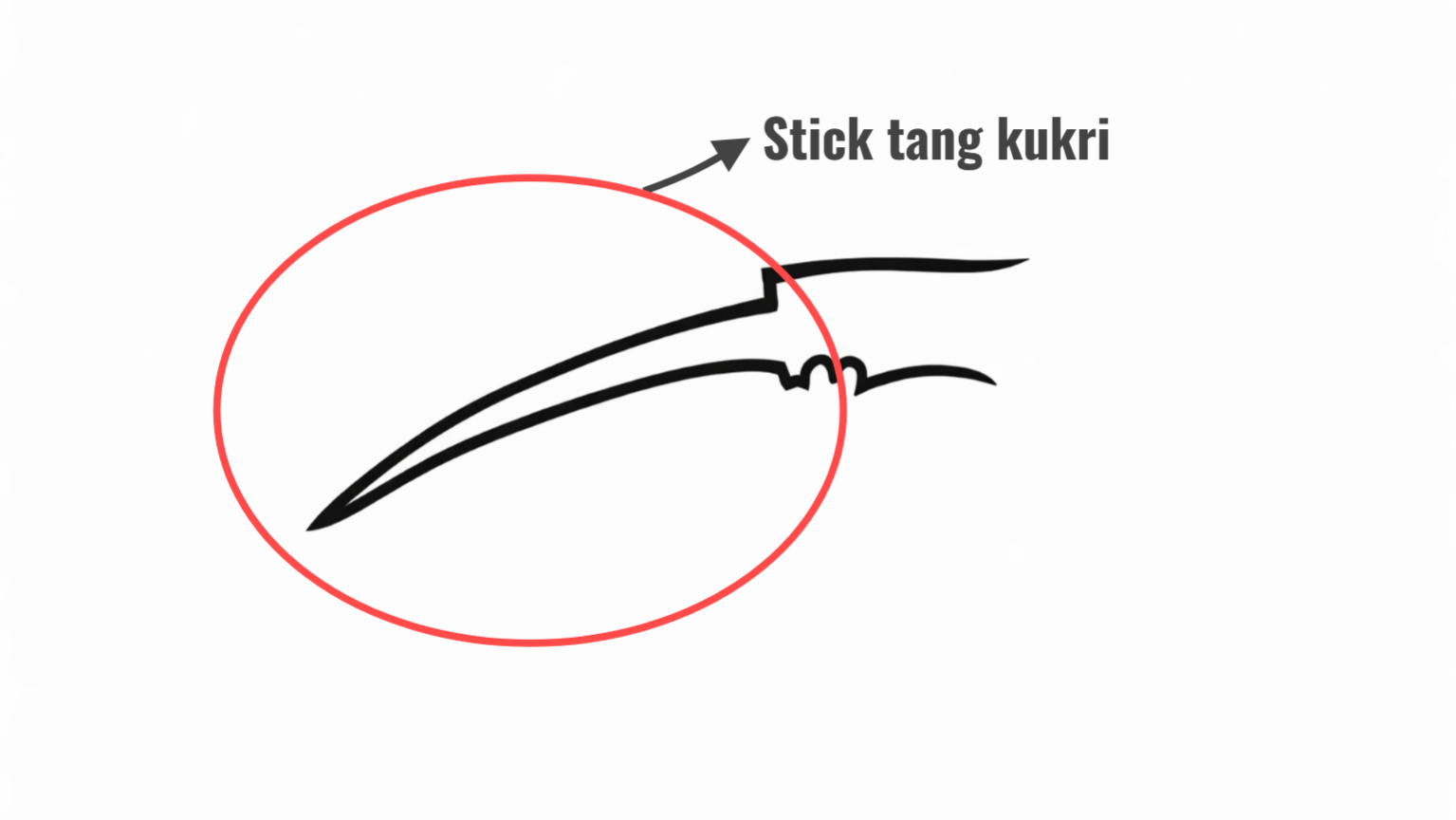

4.2 Rat-Tail Tang

A true rat-tail tang is an extended part of the kukri, often tapered till the end by hammering. The stick tang or rat tail tang kukri exceeds the handle material, and then it is pinned at the back. This tang is hammered multiple times and tapered, making it thinner and longer. The tang is often softer, which gives it a better ability to absorb shocks under stress; if it is too brittle, then it will break.

This design has emerged after partial tang kukris. Some of the kukris that had stick tangs in their original designs are the 6th GR War Serupate Kukri, Angkhola Kukri, BSI Kukri Knife, MK1 Khukuri, Mutant Angkhola, Neo Hanshee, etc.

Reference: ASM Handbook, Vol. 6, Welding, Brazing, and Soldering.

4.3 Full Tang Kukri

A full tang kukri extends steel the full length and width of the handle.

Advantages:

- Increased static tensile strength

- Ease of handle replacement

- Familiarity for Western users

Limitations specific to kukris:

- Higher shock transmission to joints

- Altered balance point

- Reduced fatigue damping

Instrumented studies of hand tools show that excessive rigidity increases user fatigue and long-term joint stress. In kukris, controlled flex is not a weakness—it is a functional necessity. This tang is sandwiched with the handle material and fixed with rivets and industrial glue at Himalayan blades. However, some makers only add rivets, which, in the long run, loosen the handle material.

Reference: McCarthy, T., “Impact Damping in Hand Tools,” Applied Ergonomics.

4.4 Hybrid and Encapsulated Tang Systems

Some modern makers use wide internal tangs enclosed within the handle. When forged (not welded) and properly tempered, these systems can work well—but execution quality is critical, and many commercial examples fall short.

5. Metallurgy: Steel Selection and Heat Treatment

5.1 Why Spring Steel Dominates Authentic Kukris

Traditional kukris overwhelmingly use high-carbon spring steels such as 5160. These steels offer:

- High impact toughness

- Superior fatigue resistance

- Predictable tempering behavior

Fatigue failure—not overload—is the primary cause of tang breakage in impact tools. Spring steels excel in this regime.

Reference: ASM Handbook, Vol. 1, Properties and Selection.

5.2 Differential Heat Treatment in Kukri Tangs

Microhardness testing of antique kukris shows tang hardness typically 10–15 HRC points lower than the cutting edge. This gradient prevents brittle fracture at the tang shoulder.

Mono-hardened blades lack this margin of safety and fail more violently when overstressed.

Reference: Williams, A., The Sword and the Crucible.

6. Kukri Knife Handle Construction and Tang Performance

A tang does not function in isolation. Traditional kukri knife handle construction relies on:

- Compression fitting

- Resin or epoxy filling micro-voids

- Organic materials such as wood or horn

This system prevents tang oscillation and distributes load across the handle. Many reported “tang failures” are in fact handle failures misdiagnosed by users.

Reference: Koch, R., “Failure Modes in Composite Handles,” Materials & Design.

7. Failure Analysis: Where Kukris Actually Break

Workshop repair data and metallurgical studies show failure concentrates at:

- Sharp-tang shoulders

- Weld interfaces

- Over-hardened tangs

- Low-quality handle material

Tapered tangs fail gradually (bending), while uniform tangs fail abruptly (fracture). Gradual failure is survivable and repairable; abrupt failure is not.

Reference: Peterson, R.E., Stress Concentration Factors.

8. Kukri vs Other Knife Tang Systems

Kukris behave mechanically closer to axes than knives. Axe handles rely on flex to absorb shock; kukri tangs perform the same function internally. Removing that flex increases measured strength but reduces durability and endurance.

Reference: USDA Forest Products Laboratory, Tool Impact Dynamics.

9. Choosing the Right Kukri Tang (US Market Guidance)

- Survival & chopping: forged tapered tang

- Short tactical kukris: full tang acceptable

- Martial training: balance over mass

Buyers should ask:

- Is the tang forged or welded?

- Is it tapered?

- Is differential heat treatment applied?

If these questions cannot be answered clearly, the kukri is likely decorative.

Reference: Knight, B., The Complete Guide to Knives.

10. Himalayan Blades: Why We Build Kukris This Way

At Himalayan Blades, we forge the tang as a true extension of the blade, not as an afterthought. From the very beginning, we shape it integrally during forging, long before heat treatment begins. As a result, the steel maintains continuous grain flow from blade to handle, allowing the kukri to manage shock and vibration more efficiently. After forging, we carefully heat treat and temper the tang for impact resilience, ensuring it performs under real-world stress, not just controlled conditions.

Moreover, this method is not based on theory alone. It reflects centuries of Gurkha forging tradition while aligning seamlessly with modern materials science, where controlled hardness and elasticity determine the long-term survival of a blade. Therefore, instead of chasing exposed steel or visual trends, we focus on what endures repeated use. We do not forge for appearances. We forge for balance, reliability, and longevity—because a kukri should earn trust through performance, not visibility.

11. Tang Geometry and Stress Flow in Kukris: Why Shape Matters More Than Width

When discussing kukri tang strength, most debates collapse into a crude binary: thin versus thick. This is an oversimplification that ignores how stress actually behaves in steel under dynamic load.

In impact tools such as kukris, stress does not distribute evenly. It follows the path of least resistance, flowing through the blade and concentrating wherever geometry changes abruptly. In kukris, this critical zone lies at the tang shoulder, where blade mass transitions into handle support.

A forged kukri tang is traditionally tapered in both thickness and width, creating a gradual reduction in cross-sectional area. This taper serves three structural functions:

- It reduces stress concentration by avoiding sudden sectional changes

- It allows controlled elastic flex under peak load

- It prevents crack initiation at the blade–tang junction

From a materials engineering standpoint, this design mimics the principles used in leaf springs and torsion bars, where gradual geometry transitions dramatically increase fatigue life.

By contrast, many modern “heavy-duty” kukris use uniform rectangular tangs. While these appear stronger visually, they introduce sharp internal corners and abrupt geometry transitions. Under repeated chopping, stress localizes at these corners, accelerating micro-crack formation. When failure occurs, it is sudden and complete.

This explains why traditional kukris often bend before they break, while poorly designed modern kukris snap without warning. In real-world use, a bent tang can be reforged or rehandled. A snapped tang ends the blade entirely.

Reference: Peterson, R.E., Stress Concentration Factors, Wiley.

Reference: ASM Handbook, Vol. 19, Fatigue and Fracture.

12. Case Studies: Real Kukri Tang Failures and Survivals

Case Study 1: Welded Rat-Tail Tang Failure (Modern Export Kukri)

A modern export kukri marketed as “battle ready” was returned after light wood chopping. Failure occurred cleanly at the weld interface between blade and threaded rod tang. Metallurgical inspection showed:

- Interrupted grain flow

- Incomplete weld penetration

- Heat-affected zone embrittlement

This failure mode is textbook and repeatable. The blade did not fail due to excessive force; it failed because cyclic fatigue concentrated at the weld seam.

This design violates fundamental forging principles and has no historical precedent in Gurkha kukri construction.

Reference: ASM Handbook, Vol. 6, Welding, Brazing, and Soldering.

Case Study 2: Traditional Forged Tang (Antique Kukri, ~1890s)

An antique kukri with over a century of service exhibited a slight tang bend after decades of chopping and agricultural use. The handle loosened, but the blade remained intact.

Key observations:

- Continuous grain flow from blade to tang

- Softer tang hardness relative to the edge

- Gradual deformation rather than fracture

The kukri was successfully reforged and rehandled, restoring full functionality. This illustrates the repairability advantage of the traditional khukuri tang design.

Reference: Williams, A., The Sword and the Crucible.

Case Study 3: Full Tang Kukri and User Fatigue

A full tang kukri of similar blade weight was tested alongside a traditional forged-tang kukri. While structural integrity was not compromised, users reported:

- Increased wrist fatigue

- Higher shock transmission

- Reduced endurance during extended chopping

This aligns with ergonomic studies showing that excessive rigidity increases cumulative joint stress in impact tools.

Reference: McCarthy, T., “Impact Damping in Hand Tools,” Applied Ergonomics.

13. Kukri Tang Construction in Self-Defense and Tactical Contexts

In self-defense discussions, tang construction is often overlooked in favor of blade length or edge sharpness. This is a mistake.

A kukri used defensively must remain structurally reliable under:

- High-stress grip pressure

- Off-axis strikes

- Unpredictable contact angles

A tang failure in such a context is not merely inconvenient—it is catastrophic. From a legal standpoint in the US, a tool failure during a defensive encounter can complicate post-incident scrutiny. Questions may arise regarding equipment choice, reliability, and responsibility.

A properly forged kukri tang provides predictable structural behavior, reducing the risk of sudden failure. This predictability matters not only physically, but also legally and ethically. Choosing a kukri with proven tang construction is part of responsible ownership.

While full tang kukris may appeal psychologically in tactical scenarios, they are not inherently superior. What matters is forged continuity, heat treatment, and geometry, not exposed steel.

Reference: Knight, B., The Complete Guide to Knives.

Reference: Grossman, D., On Combat (contextual stress effects).

14. Buyer Inspection Guide: How to Evaluate Kukri Tang Quality Without Cutting It Open

For buyers—especially in the US market—evaluating kukri tang quality before purchase is challenging. However, several indicators are reliable:

Signs of a Properly Forged Tang

- The maker can clearly explain the forging process

- No mention of welding or threaded rods

- Balance point sits forward, not neutral

- Handle fit is tight, with no hollow sound

Red Flags

- Claims of strength without metallurgical explanation

- Overemphasis on tang visibility

- Vague or evasive answers to construction questions

A trustworthy maker speaks confidently about what is inside the handle, not just what is visible outside it.

15. Why Himalayan Blades Rejects Tang Marketing and Follows Evidence

At Himalayan Blades, tang construction is approached as structural engineering, not aesthetics. We forge tangs integrally, taper them deliberately, and temper them for impact resilience. Our choices are guided by:

- Historical survivability

- Metallurgical principles

- Real-world failure analysis

This philosophy aligns with authentic Gurkha knife tang construction and modern materials science alike. It is slower, more demanding work—but it produces kukris that endure.

16. Final Synthesis: Understanding the Kukri Through Its Tang

Across centuries, cultures, and technologies, one lesson remains constant: the tang reveals the truth of the blade.

A kukri’s curve may inspire awe. Its edge may impress. But its tang determines whether it survives real use or fails under it.

Traditional kukri tang construction was not accidental, primitive, or outdated. It was the result of generations of empirical refinement—steel shaped by necessity, not marketing. Modern interpretations that respect these principles succeed. Those who ignore them do not.

For anyone serious about kukris—whether for survival, martial training, self-defense, or historical appreciation—understanding tang construction is not optional. It is fundamental.

17. Conclusion: The Tang as the Kukri’s Structural Truth

The tang reveals whether a kukri was engineered for real use or superficial strength. History, metallurgy, and failure analysis all converge on one conclusion:

The strongest kukri is the one whose tang you never see—but can always trust.

References

- Egerton, W. – Indian and Oriental Arms and Armour

- Rawson, P.S. – The Indian Sword

- Verhoeven, J.D. – Steel Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist

- Williams, A. – The Sword and the Crucible

- ASM Handbook, Vols. 1 & 6

- Peterson, R.E. – Stress Concentration Factors

- Royal Armouries, Gurkha Kukri Collections

- Journal of Materials Processing Technology

- Applied Ergonomics

- USDA Forest Products Laboratory Reports